This article is part of a series:

- Reflections on 3 years of (Transfer) Wise | Part I: Mission and Values

- This Article

- Reflections on 3 years of (Transfer) Wise | Part III: All about People

- Reflections on 3 years of (Transfer) Wise | Part IV: The Engineering Organisation

- Reflections on 3 years of (Transfer) Wise | Part V: Other Strategic Topics

- Reflections on 3 years of (Transfer) Wise | Part VI: Not just about Work

- Reflections on 3 years of (Transfer) Wise | Part VII: Closing Thoughts

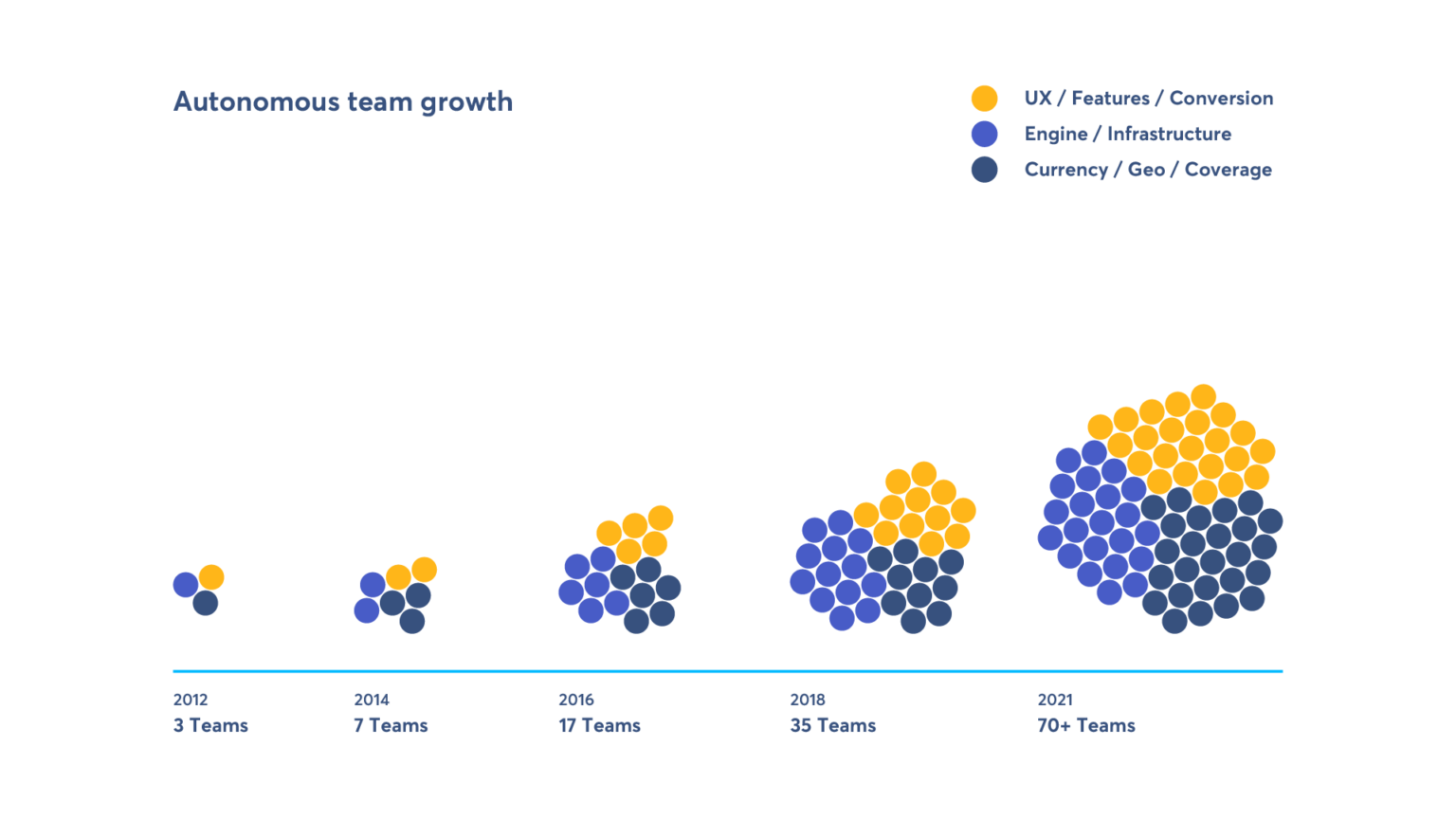

(^ Autonomous team growth, 2012 - 2021 ^)

To me, the culture of Wise was anchored on two foundations: feedback and autonomy. Jessica had a good writeup on the former already. I’d like to single out autonomy which had a profound impact on how Wise operated.

I am a big fan of autonomy and its application at Wise. Towards the latter part, I look at the areas where autonomy may fall short and offer my opinions on those areas.

Always bottom-up, rarely top-down

Wise operated in (what I call) an extreme form of autonomy, where product teams who had the fullest visibility of what customers needed in their respective areas drove product development. Most if not all people at Wise subscribed to autonomy as the way of working, from the leadership to individuals working at ground zero. Many people at Wise crossed paths with Kristo, and whenever you asked him a question in your area of expertise, his usual response was what do you think? which summed up the autonomous culture and how hard leadership were pushing for it.

It not only permitted people to make independent, and hopefully informed decisions based on their visibility, but also pushed them to do so. It favoured a certain type of people who were entrepreneurial and independent-thinking. In return, they were rewarded with a huge amount of autonomy to execute, as long as it was within the framework scoped by the mission and the values.

However, it was not easy to acclimatise to it if not coming from a similar organisation. I thought of myself as being entrepreneurial, but it took me 6-12 months to truly feel adapted to the type of autonomy in action at Wise. I wish somebody could tell me that working at Wise was the equivalent of running your startup with a safety net; You never wait for commands from above to operate.

It made scaling up easy too. In a top-down organisation, the leadership’s bandwidth would be increasingly squeezed while scaling. A counter-measure would be to add more layers to the organisational hierarchy to ease the congestion. At Wise, a bottom-up approach of having more product teams as a result of more product features was easy and natural because these were the people who were going to make not only tactical but also strategic decisions. As for leadership and senior managers, they were unlikely and unwilling to make these decisions anyway due to their limited visibility. It also helped keep the organisation flat. To scale, the challenge was about having the right people working on the right product features and letting them loose, which was a hiring and retention problem that was well-defined and therefore easier to solve.

The fear of ruining autonomy was real

Like the mission and the values, people felt strongly about the autonomy culture and defended it rigorously. It was understandable and well-intentioned; however, I felt that the fear of showing any sign of undermining autonomy overcame common sense at times.

An example was the introduction of OKRs. It was on the back of the consensus that although KPIs served the company well in the early days, a new framework should be introduced in place of it to see the company through the next phase of growth. The initiative was well received by all. However, it quickly became clear to me (and some others) that without a set of company-wide, top-level OKRs, it was difficult for product teams to come up with their OKRs without the prerequisite. It also did not help teams coordinate on respective OKRs in overlapping areas. The situation had since improved upon feedback. My take for the interesting approach on the first go was that people were afraid to be seen as breaking the promise of autonomy, even when it was breaking the fundamental piece of OKRs.

In software engineering, we all start following rules. When we gain experience, deciding when to break the rules becomes increasingly important. Similarly when a company grows, when and how to break away from existing approaches is always a challenge, not to mention autonomy at Wise which was the key to almost everything people did here.

Autonomy should not be the silver bullet

One analogy I often use is how products at Amazon Web Services are developed. It is clear from the outside, judging by their cloud product line that they operate in a similar, autonomous manner where each product team take charge of one cloud service. Applying Conway’s law, from their somewhat disjoint AWS Console UX, and overlapping purposes in some of their cloud services, I could sense that their two-pizza teams suffer the same team-silo problem I witnessed while at Wise.

Compared to AWS, whose product-to-team assignment could not have been clearer thanks to the diverse nature of each AWS service as a product, product teams at Wise inherently had more or less overlaps in both product features and underlying implementations. Running in silos was common. Lately, there were efforts made to be more collaborative at individual and team levels, which in my view were nice to see out of people’s awareness and good intention but without being guided by a framework or process, they had limited impact on improving the silo situation. It wasn’t until OKRs were introduced company-wide, where organisational units’ goals and executions were made highly visible, that silo stopped being a painful issue.

Autonomy was also prone to misinterpretation at times. A typical offending scenario was an individual or a team pursuing a misaligned goal often used autonomy as a defence to justify the behaviour. It was called out sometimes but tolerated other times, which had a negative impact not only on the offending individual or team, i.e. building the wrong thing, but also on others witnessing the behaviour, who in the unluckiest event might misjudge the true meaning of autonomy and follow the wrong examples.

To sum up, my ideal kind of autonomy would be:

- Visibility-based autonomous teams: whoever has the fullest visibility should take the lead and act (in this case product teams usually act on a specific set of features while leadership may lead org-wise initiatives that require broader visibility and understanding of the subject matter);

- Feedback on what to build beforehand, and retrospect on how it went afterwards;

- Be transparent throughout and be accountable for the result.

Interestingly, Nilan’s blog post is still relevant after so many years.